Você está na versão anterior do website do ISA

Atenção

Essa é a versão antiga do site do ISA que ficou no ar até março de 2022. As informações institucionais aqui contidas podem estar desatualizadas. Acesse https://www.socioambiental.org para a versão atual.

Indigenous brigades facing fire on the front line

Friday, 08 de November de 2019

Fire management

Esta notícia está associada ao Programa:

In different parts of Brazil, indigenous people hired by PrevFogo work to prevent and fight forest fires

At night, or in the wee hours, before the sun rises, the indigenous firefighters go to work. This is when the temperature of the burning forest is more bearable and the air humidity, a little higher, making it possible to work. The location of the hotspot is captured via satellite by the National Institute for Space Research (Inpe) and transmitted to the base, where the indigenous firefighters await. They hike into the forest, equipped with their backpack pumps, fire swatters and leaf blowers.

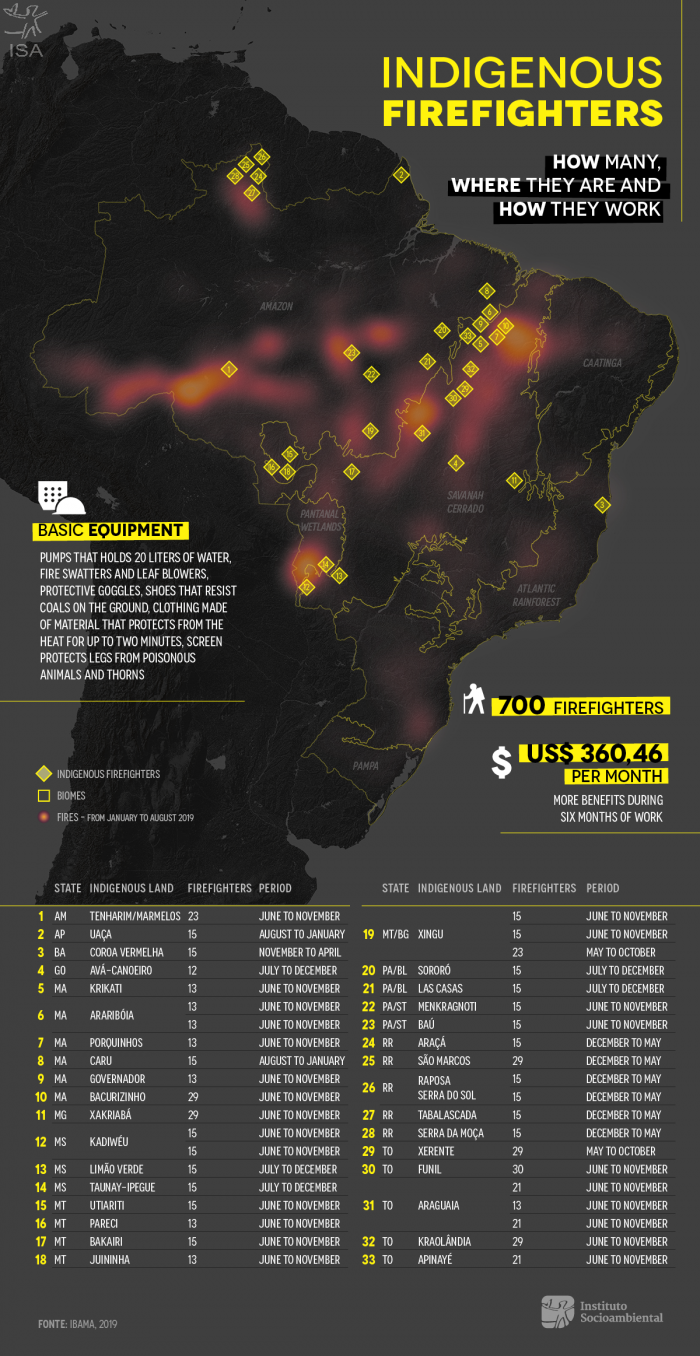

Throughout Brazil, 700 indigenous firefighters were hired in 2019 by PrevFogo, a program created by the Brazilian Institute of the Environment (Ibama). In the Legal Amazon, the fire brigades form one of the main instruments for combating forest fires, which have destroyed around 435,000 hectares in the last 8 months and led to an international political crisis. These firefighters are spread over 34 indigenous lands of the Tenharim, Paresí, Gavião, Xerente, Guajajara, Krikati, Terena, Kadiwéu, Xakriabá, Javaé, Karajás, Pataxó, Kayapó and ethnic groups of the lower, middle and upper Xingu who, when the rain does not come, help to put out the flames that ravage Brazilian forests.

It is their concern for the forest and deep knowledge about their own territory that makes the indigenous firefighters stand out. “They are more committed to prevention and firefighting activities than firefighters hired in the municipalities,” explained Rodrigo Faleiros, in charge of hiring at PrevFogo. The Federal Fire Brigade Program has existed since 2013. “They know the territory well and all the aspects involved in firefighting such as, for example, surviving in the forest, finding their way and understanding the effects of the fire,” said Faleiros.

The challenge for these firefighters is by no means small. In August of 2019, there was an increase of 182% in the total number of hotspots affecting indigenous lands in the Legal Amazon, compared to the same period in 2018.

Pedro Paulo Xerente manages one of the fire brigades. A member of the Xerente ethnic group, he recounts stories that he experienced in firefighting this year. “The fire is never the same. Regardless of how much we prepare, we’re never prepared enough to understand it,” he said. “There was a day that the fire spiraled out of control and came at us very quickly, and we had to jump from a ledge into the river,” he recounted. “A short time later we were all smiling, and saying let’s go back to put out the fire.” To try to understand the dynamics of the fire, he and his firefighters asked for help from the elders of the community. In August 2019, 75 separate fires were recorded on the Xerente Indigenous Land, 400% more than the same period last year.

To put out the fires, the brigade members carry pumps on their backs, a type of backpack that holds 20 liters of water. They also use fire swatters and leaf blowers. Uniforms are specific to the work—protective goggles, and shoes that resist coals on the ground, in addition to clothing made of material that protects from the heat of the fire for up to two minutes. A screen protects legs from poisonous animals and thorns.

In the Cerrado, and in transition zones with the Amazon forest, fire has always been used by indigenous peoples for productive activities and hunting. “However, with the increase in deforestation, climate change and the prevailing political context, the number of hotspots that have become forest fires has increased" said Antonio Oviedo, a researcher at ISA. An element that contributes to the increase in fires is the progressive loss of humidity in the forest due to degradation. An example of this are the indigenous lands in the state of Maranhão, where a large part of the forest cover has already been severely degraded by illegal logging, making traditional practices that use fire riskier than before. “In addition, the vast majority of hotspots on indigenous land occur in invaded areas and where there are illegal mining operations,” said the researcher. These invaded areas are responsible for most of the deforestation within the indigenous lands. According to data from Deter-B, the indigenous lands present an increase of 38% in deforestation alerts, compared with the first half of 2018, and just 13 indigenous lands are responsible for 90% of these alerts.

This is the case of the Apyterewa Indigenous Land in Pará, which presented an increase of 529% in the number of hotspots compared to 2018. The increase is related to the growth in deforestation: according to Inpe, the deforestation alerts in the area grew 147% between April and August of 2019, compared to the same period last year. The Apyterewa Indigenous Land was established in 2007, but around 80% of the territory is illegally occupied by non-indigenous people. Operations to expel intruders have been ongoing since 2011, but even today their eviction from the territory has not been concluded.

On the Tenharim-Marmelos Indigenous Land, in southern Amazonas, for example, criminal arson occurred in the area surrounding the reserve, in settlements and invaded areas, and then entered the reserve, according to Helio Moreira, a PrevFogo instructor who works with the Tenharim. The indigenous land has areas of Amazonian fields where fire spreads more easily. “Non-indigenous dwellers are very close to the borders of our territory,” explained Amaury Tenharim, who coordinates his people’s fire brigade. There are 29 indigenous people who have undergone the selection process (tests for physical fitness and with agricultural tools) and training.

The work of the brigades, however, is still small compared to the scope of the fires. PrevFogo suffered from a funding crisis that has affected the government since 2015 and that has led to cuts in spending in all areas. This slows the hiring of more firefighters, and the consolidation of a career plan for those already working. Today, an indigenous fire brigade member earns one and a half times the minimum monthly salary, in addition to benefits, and the duration of the contract is six months, which covers the dry season. “The best public policy to deal with the issue of fire is PrevFogo, and it is designed to work both with fire prevention and firefighting. But it needs to be strengthened with funding and expanded engagement with local communities," said Adriana Ramos, a member of ISA.

Another challenge is dialogue and incorporation of indigenous practices. Since its work began with the indigenous people, PrevFogo has adopted different management practices and traditional knowledge in its activities. But much remains to be done in this process—learning about the work that has already been done to deal with fire in each territory, and make progress in partnering with the indigenous people based on this vision. Each ethnic group has its own way of working. In the Xingu, the indigenous people have been able to drastically reduce fires on their land. See how here.

“The effects of climate change have become manifest with each passing year,” explained Sidney Silva, a PrevFogo agent who works on indigenous lands in Tocantins. According to him, every year, the first rains come at the beginning of September, marking the end of the dry season. “However, we have already entered September and it is still hot, dry and windy,” he said, in an interview with ISA. “The fire knows no border, and the wind allows the fire to escape the deforested area,” explained Pedro Xerente. According to him, the temperatures are higher and the winds stronger, which help the fire to spread.

Fire management

Since the agency began working with indigenous people, PrevFogo has changed its way of approaching and viewing fire. Not only the way it is fought, but as an element of the landscape, above all in regions of the Cerrado. This has led to an expansion of strategies to counter the fires.

A result of this conceptual change is the prescribed burnings, which serve a preventative function. The idea is to have controlled burnings at the start of the dry season, when the humidity in the forest is still high, and the chances of the fire spreading is lower. These burnings, managed by the fire brigade, consume accumulated dry organic material in these areas, reducing the fuel available that can help the fire to spiral out of control during severe dry spells, when the air humidity is very low and the vegetation is even drier.

In this work, traditional knowledge of fire management and above all the contribution of community elders are essential. “At the start of the dry season, the elders tell us where to burn, what to burn and when to burn,” said Pedro Xerente. This can influence the fruiting of the trees, for example.

“When you burn at the right time, you ensure flowering, which shelters wild animals and fruit. The best way to protect the forest is to do the prescribed burning at the right time, before the most severe dry period,” explained Sidney, a management agent.

The creation of firebreaks is another strategy to keep the fire from spreading. Firebreaks are clearings opened in the forest that are free of organic material. The fire finds an “empty space” and, without fuel to burn, extinguishes itself. The firebreaks are important primarily in the burning of the traditional garden plots, created before planting, and that many times are also accompanied by the fire brigade members. “The fire also brings us life. It is through fire that we can make the garden plots, which produce fruit, which becomes food, and then organic material, which feeds the soil. It is the fire that makes life happen,” said Pedro Xerente.

The improved practices of the fire brigades of Prevfogo require constant interaction and exchange of experiences between indigenous and non-indigenous fire brigade members. The monitoring of results obtained in the fire prevention and firefighting activities provide lessons that can improve future actions.

Clara Roman

ISA

Imagens: