Você está na versão anterior do website do ISA

Atenção

Essa é a versão antiga do site do ISA que ficou no ar até março de 2022. As informações institucionais aqui contidas podem estar desatualizadas. Acesse https://www.socioambiental.org para a versão atual.

Rio Negro bids farewell to its Feliz

Monday, 18 de May de 2020

Esta notícia está associada ao Programa:

Feliciano Lana, the man who translated Rio Negro's landscapes into art, in the density and strength of the senses they have for their indigenous people, has died

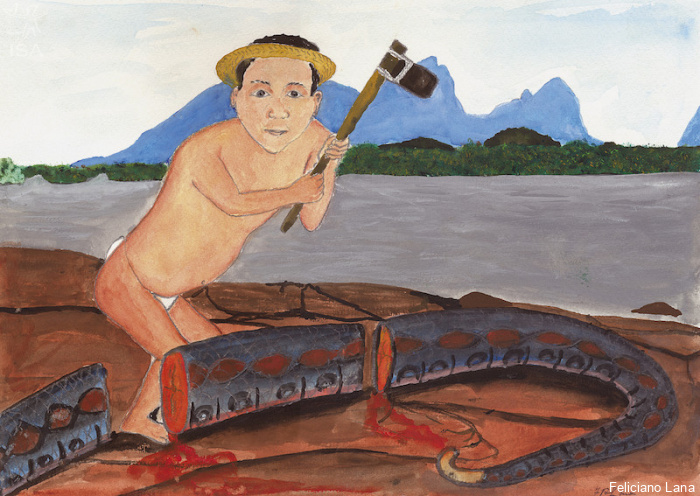

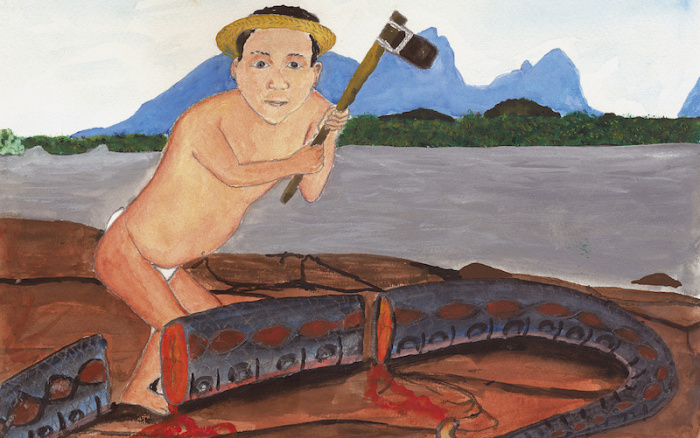

Feliciano “Feliz” Pimentel Lana passed away 4 o’clock yesterday morning, in São Francisco, a community located on the Upper Rio Negro, where he was buried, today, in the presence of his family. At 83 years of age, the Desana artist, who possessed an unmistakable style, leaves an extensive body of work, which had been disseminated through many publications and collections of domestic and international institutions, making him a point of reference for the indigenous of the Rio Negro. He was an expeditious and versatile artist, expressing his detailed knowledge of the narratives, history and landscapes of the northwest Amazon in his drawings and paintings.

Feliciano was born into the Desana of São João, from the middle Rio Tiquié, and given the sacred name of Sibó or “child of the sun.” “My grandmother used to carry me to the garden plot,” he recounts, when he was still an infant. “I remember clearly being on the trail to the plot with the rain falling. And I realized that she was carrying me on her shoulders. This is where my reflections on life come from. Little by little I became a boy. She died after I entered school” (from a recent interview with the anthropologist Thiago Oliveira).

Feliz followed the path of his generation: he studied at the Pari-Cachoeira school, when it was still under construction, where he helped, as did all the students, to build it—in those days the Catholic missionaries held much sway in the regions and imposed strict educational practices; after completing the sixth grade, he went to work as a rubber tapper in Colombia, like many other relatives from Tiquié, where he remained for five years; upon his return he married Joaquina Machado, a Tukano from Pari-Cachoeira.

It was during this time that he began to work with the Lithuanian priest Casimiro Béksta, a recent arrival to the region who was very interested in indigenous narratives and shamanism. In one of the first works that Feliciano gave him, concerned about the difficulty in expressing certain ideas, he decided to draw some of the episodes described by his mother-in-law, an old sage. This mark the beginning of his art, an expression of the narratives of his people, an art without pretention that revealed the world of the Desana in a unique way. This work of recording the knowledge of the Kumua (specialists in ritual accoutrements) at the request of the missionary ended up being another source of learning for Feliciano.

In the 1980s, wildcat gold mining in the Traíra Mountains—which could be reached by trails in the forest from tributaries of the Tiquié—and harassment from the mining companies, in addition to the growing military presence in the region, brought significant impacts and upheavals to the communities of the Rio Tiquié. Many of the locals ended up working in mining or producing flour to supply those residing there. Gold, initially abundant, attracted many merchants, who arrived there, along with their merchandise, by negotiating with river traders.

The first time I met Feliciano, in 1993, he was still in São João. I was working upriver, with the Tuyuka, but I stopped to pay him and take delivery of some drawings for Berta Ribeiro. She had worked in this community, primarily with Luis Lana and his father, having also contributed to a book of narratives, “Antes o Mundo Não Existia” [Before the World Existed], first published in 1980, and most recently in 2019.

Move to São Gabriel

Feliciano moved to São Gabriel da Cachoeira in the mid-1990s, residing with his family atop the hill known as Pedra da Fortaleza, where they were the only residents. The location sits near the already unrecognizable ruins of a fort built by the Portuguese over two centuries before, in 1763, which was strategically positioned at the narrowest point of the Rio Negro. Precisely because of this, a long time ago, according to the narratives of origin, this location was chosen by the “People of the Transformation” to capture and kill the monster snake known as Diadoe—the snake of the Traíra, by placing a giant trap there, which Feliciano illustrated with different nuances.

He never tired of painting the vast, incredible landscapes of the Rio Negro and its mountains, which can be seen from the fort atop the hill. He knew the name of the home mountain—Basebo, Wariró and their daughters. Dona Joaquina, who was older than him, was also knowledgeable and taught him a great deal.

In time, Joaquina passed away, and Feliciano had to leave the fort and move to Areal, a neighborhood that was emerging on the outskirts of the city, a more distant and much less pleasant location. But he persisted and continued to paint and heal, since he was recognized and sought out as a healer.

Calm and generous, ready for new challenges and to pass on his knowledge, Feliz produced significant, expressive work on the cosmology of the Tukano peoples, which became almost omnipresent in the research of anthropologists, historians and artists when studying the Rio Negro. His works can be found in a variety of institutions, including Museu de Arte de Belém, Museu da Amazônia and the British Museum, with which he was recently collaborating.

They were creating an inventory of publications that feature his drawings and paintings, which total close to one hundred, in Brazil and abroad, in addition to exhibitions and animations.

Feliciano did not ignore the theme of labor. In fact, he addressed all themes: plants of the garden plots, trees, fish, artifacts and utensils, work scenes, portraits of men and women and their activities, feelings and conditions, festivals, rituals, elements cited in the blessings. However, his predilection was to illustrate mythological narratives, where he expressed, in a creative manner, concepts and perspectives central to these peoples, at times coded but at the same time easy to understand.

Feliciano assiduously frequented and maintained a close relationship with Instituto Socioambiental (ISA) in São Gabriel da Cachoeira, where he spent time with team members and other partners and researchers who visited and lodged there, in addition to contributing to their publications and organizing some drawing workshops.

With the announcement of the arrival of the pandemic in the Upper Rio Negro, he spoke of his concern about being older and more vulnerable, and that he would recede into the interior, where his children lived. As occurred in São Gabriel, with its banking services and commerce, however, many delayed leaving the city. When the first cases of community transmission emerged, the seriousness of the situation became evident.

In Areal, Dabaru and Graciliano alone, neighborhoods adjacent to where he lived, up until yesterday there were already 55 confirmed cases and six deaths. He left the city with Covid-19 symptoms, and succumbed to the disease in São Francisco, according to reports that arrived by radio.

Translation: Glenn Johnston

Aloisio Cabalzar

ISA

Imagens: