Você está na versão anterior do website do ISA

Atenção

Essa é a versão antiga do site do ISA que ficou no ar até março de 2022. As informações institucionais aqui contidas podem estar desatualizadas. Acesse https://www.socioambiental.org para a versão atual.

What changes (or what’s left) for the quilombos with president Bolsonaro’s reforms?

sexta-feira, 01 de Fevereiro de 2019

Esta notícia está associada ao Programa:

The rural caucus is now in charge of land titling. This second report on ministerial restructuring prepared by ISA shows where the policies for quilombolas have gone

Amongst the many offensive phrases against minorities that have been said by Jair Bolsonaro, one of the most symptomatic was stated at the Hebrew Club in Laranjeiras, a neighborhood of the city of Rio de Janeiro, on March 4th, 2017.

“I’ve been to a quilombo. The skinniest African-descendant there weighed seven arrobas [a unit of measure used to weigh cattle, equivalent to 15kg]. They don’t do anything! I think they don’t even serve as procreators any more”, he affirmed. He also added that, if elected president, there wouldn’t be “a centimeter [of land] demarcated” for indigenous and quilombola communities. In September, the Federal Supreme Court (STF) rejected the accusation of racism filed by the Federal Attorney General (PGR) against the then federal representative.

In the history of Brazil, the black slaves who rebelled against the owners they served and took refuge in the woods or other remote and protected places are called "quilombolas." This focus of resistance against slavery was then called "quilombo". The formation of the "quilombos" begins soon after the arrival of the first enslaved Africans to Brazil, in the XVII century, extending until after the end of the slavery, already in the XX Century.

After centuries of exclusion and violence, the quilombolas are amongst the most vulnerable communities in the country, victims of a structural racism, at the margin of government policies and with an enormous land tenure regularization debt to be settled. In the most drastic ministerial reform in nearly 30 years, implemented during the first days of the new administration, Jair Bolsonaro, now president of the country, has decided to subordinate the recognition of territories for these communities to the rural caucus, which has a historical opposition to the democratization of access to land in the country.

Apparently, the objective is to keep the promise made in Rio in 2017. This second report prepared by ISA on the restructuring of high-level agencies in the new federal administration shows how and why land titling is definitely threatened, after progressing at an extremely slow pace over the past few years.

The rural caucus in control of land titling

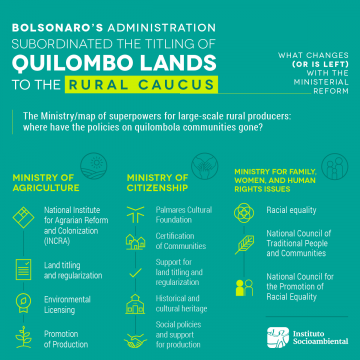

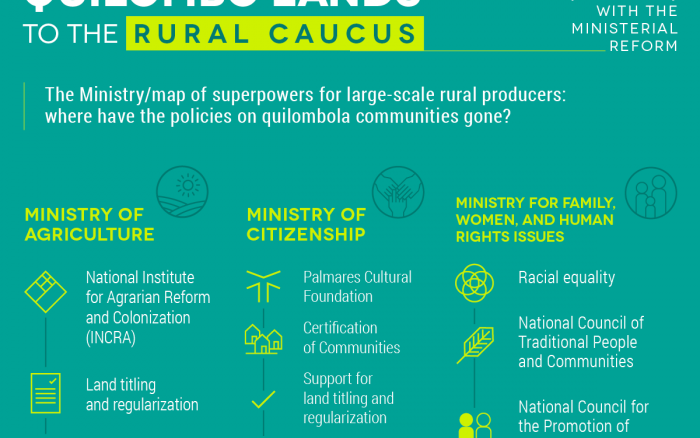

The official recognition of quilombos and Indigenous Land (IL) is now the responsibility of one of the super-ministries of the new administration, the Ministry of Agriculture (Mapa). The directory also incorporated the attribution of evaluating and deliberating on environmental licensing for projects that affect these areas.

Responsible for formalizing quilombos in the federal context, the National Institute for Agrarian Reform and Colonization (Incra) is now tied to the new Special Secretariat of Land Tenure Issues (Seaf) under Mapa, led by the licensed president of the Democratic Union of Rural Producers (UDR), Luiz Antônio Nabhan Garcia.

The UDR is a conservative organization which arose in the late 1980s in opposition to agrarian reform and the movements of peasants and rural workers. It also fights against the recognition of land for indigenous and traditional communities. Today, even leaders of the rural caucus don’t consider it as being representative of the agribusiness.

“Signs show that the intention is to bury the process of land titling for quilombola territories, reduce the status of Incra, a strategic agency not only for land titling, but also land tenure governance in the country”, warns Denildo Rodrigues de Moraes, of the National Coordination of the Articulation of African-Descendant Rural Quilombola Communities (Conaq). “This will allow [large-scale] farmers to do as they wish in the process of land occupation and illegal land squatting”, he criticizes.

There hasn’t been any confirmation on changes in Incra’s structure, but the information that has been circulating among public officials is that the tasks of identifying areas and manifesting opinions on licensing would remain within the agency. A source from within Incra bets that Normative Ruling (NR) 57/2009 and Decree 4,887/2003, which rule the recognition of quilombos, will be modified soon.

It isn’t clear what the role of Incra will be”, comments Lúcia de Andrade, executive coordinator of the Comissão Pró-Índio in São Paulo (CPI-SP). She considers that it is still early to evaluate the consequences of the new ministerial layout, but fears there will be political interference in the initial stages of the complex procedure of quilombo recognition, for example in the decisions on disputes related to identification studies. “This is where the conflict is most intense”, she points out.

A proposal suggested by the Minister of Agriculture, former president of the rural caucus, state representative Tereza Cristina (DEM-MS), is the creation of an interministerial council to analyze the regulation of ILs and quilombos. In this case, even more interests would influence the decision on these processes, such as those from mining and energy companies.

Another change made by the Bolsonaro administration was the relocation of the Palmares Cultural Foundation (FCP) to the Ministry of Citizenship, which incorporated several attributions of the Culture and Social Development directories (see infographic). FCP is responsible for the certification of quilombola communities, the first step needed to initiate the procedure of land tenure regularization within Incra.

Review of processes

Nabhan Garcia has repeatedly said that he will review the processes of recognition of ILs and quilombos due to supposed “ideological” influences and irregularities. The secretary has not gone into detail as to how that will be implemented.

The matter has already been debated within the STF. “Self-definition made by the quilombola community is only the starting point of a procedure which – I’ve counted – is carried out through a series of 14 steps, which includes an anthropological report, manifestations from Incra and all stakeholders. The idea that there could be fraud is a bit imaginative”, affirmed minister Luis Roberto Barroso during the trial on the constitutionality of Decree 4,887, carried out in February 2018. “We would need the quilombola community to create a purely imaginative society to argue there was fraud. They would have to document a type of economic production, relationships with ancestors, simulate cemeteries you normally find in these communities”, the minister highlighted.

“What they’re saying with this action [of reviewing the processes] is: ‘we aren’t going to advance in land titling, we are going to retreat’. It is much more of a political action than a legal one”, analyzes Fernando Prioste, legal advisor for Terra de Direitos. He highlights that, with the notorious bias of the new government against the recognition of territories, the trend is that they will modify legislation and look for administrative loopholes to curb the procedures. “They’re going to find any hindrance, small or large, legal or illegal, to stop land titling, especially where there is conflict”, he adds. Prioste believes the first targets will be the areas of interest of the rural caucus politicians.

The Mapa press office responded to ISA reporters that Nabhan Garcia “has informed that he has not received the entire documentation” on the theme and, thus, would not be available for an interview.

Demand for land

The demand for quilombola land is more than fair. Two-hundred-forty-one titles have already been granted in Brazil, around 0.1% of the national territory or nearly one million hectares – 78% of this total was granted by state governments, 19% federal, and about 3% in partnership between both (see graph). Nearly 16.1 thousand families, from 300 communities, live in these areas, according to Incra.

Today, there are 1,716 processes being analyzed by Incra, but 84% of them do not have the Technical Identification and Delimitation Report (RTID) officially published. This document presents a proposal for boundaries. The area covered in the 284 processes that do have these studies finalized adds up to nearly 2.4 million hectares – around 0.2% of the national territory. There are 32.5 thousand families waiting for the regularization of these lands.

Meanwhile, Brazil continues to be one of the countries with the greatest concentration of land in the world. Only 93 thousand large-scale farms – or 1.6% of the total properties – concentrate 47% of the total area of rural properties or nearly 30% of the national territory. The data comes from Incra.

Land titling is the last phase of the land tenure procedure. It begins with the elaboration and publication of the RTDI, followed by the publication of a decree by Incra, and, then, with a presidential expropriation decree.

The process of recognition of quilombos stagnated in the Dilma and Temer administrations. In addition, the opening of new procedures decreases year after year.

FCP has certified 3,212 communities, which would encompass nearly 1.2 million families. There is no official estimate, however, on the total number of territories and population. Conaq affirms that there are 16 million quilombolas in the country.

The worst part is that Incra’s budget has been decreasing drastically. Between 2012 and 2018, the actual expenses with process analyses and expropriations have plummeted from BRL 51.6 million to 2.7 million, a decrease of nearly 94% (see graph). The situation tends to worsen due to the ceiling of public spending and the fiscal austerity of the new administration.

Increase in conflicts

“I fear the setbacks in regularization processes which are already moving at a very slow pace, but I’m especially worried about the consequences, which will increasingly lead the quilombola population to more social exclusion and lack of government policies”, comments Raquel Pasinato, coordinator of ISA’s Vale do Ribeira program.

The delay in land titling widens rural conflicts. Denildo Moraes explains that, in light of this situation, in order to survive, many communities have tried taking back land that was stolen in the 1970s and 1980s. On the other hand, [large-scale] farmers react or insist on remaining in quilombola areas. The situation is especially worrisome in Pará, Maranhão, Bahia, and Minas Gerais.

Between 2008 and 2015, 16 quilombolas were murdered, an average of two per year. In 2016, 4 were killed and, in 2017, 18, an increase of 450% with respect to the previous year. In total, 38 people were killed during this period (read publication). Moraes is worried with the publication, this week, of a decree issued by Bolsonaro that has loosened the norms for the possession of weapons. To him, the measure tends to increase rural violence. Furthermore, Nabhan Garcia insists he will not dialogue with movements that promote occupations.

Environmental licensing

Another change that is considered worrisome under the ministerial reform was the allocation of the attribution of issuing opinions on environmental licensing of projects that impact ILs and quilombos to the Ministry of Agriculture. Up to this point, this was the role of the National Indigenous Foundation (Funai) and FCP, respectively.

The two agencies were responsible for evaluating the impacts on these populations and for conceding the licenses. They have the technical ability to deal with the subject, with many years of experience and investment to qualify the public officials. Mapa does not have a team specialized in this area.

“The change is technically and legally wrong. In addition to the clear conflict of interests, subordinating the fundamental rights of these minorities to the economic interests of specific sectors violates the Democratic State governed by rule of law”, alerts ISA lawyer Maurício Guetta. “The conflicts, impacts, and rights violations will continue to exist. Ignoring them will result in damages not only to these populations, but to businessmen as well, with the increase of legal uncertainty”, he concluded.

Promotion of production and racial equality

The ministerial reform also includes the coordination of policies to foster production in traditional communities and agroextractivism among the competencies of the Department of Productive Structuring of the Department of Family Agriculture and Cooperativism of the Ministry of Agriculture, initiatives that impact the quilombolas.

The Ministry of Family, Women and Human Rights Issues, led by the controversial pastor Damares Alves, incorporated areas and competencies of the former Ministry of Human Rights, such as the Secretariat for Promotion of Racial Equality Policies (Seppir), the National Council for the Promotion of Racial Equality and the National Council of Traditional Peoples and Communities, agencies that also influence quilombo initiatives.

Oswaldo Braga de Souza

ISA

Imagens: