Você está na versão anterior do website do ISA

Atenção

Essa é a versão antiga do site do ISA que ficou no ar até março de 2022. As informações institucionais aqui contidas podem estar desatualizadas. Acesse https://www.socioambiental.org para a versão atual.

Deforestation in the Xingu river basin advances with the Bolsonaro government and puts at risk a 'green shield' against the desertification of the Amazon

segunda-feira, 19 de Abril de 2021

Breaking connectivity in the Xingu Corridor puts the Amazon at risk

Deforestation exploded

Xingu Protected Areas Corridor: diversity, water and shield against destruction

Esta notícia está associada ao Programa:

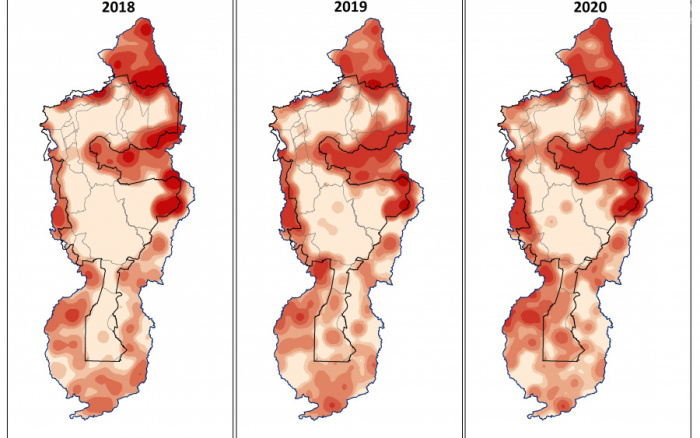

Monitoring of the Xingu + Network shows that, between 2018 and 2020, 513,500 hectares were deforested in the Xingu basin, equivalent to six times the city of New York (USA). One of the epicenters was a forest strip that maintains the humidity of the biome

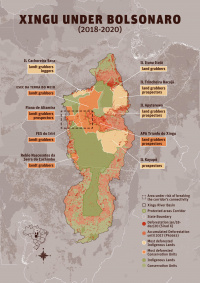

The results of three years of monitoring Sirad X, the deforestation detection system of the Xingu + Network, reveal an intensification of conflicts and disputes over land and natural resources in the Xingu Protected Areas. Deforestation, illegal mining, fires, land grabbing and the impacts of major infrastructure works threaten the Xingu and its peoples. [Access the study "Xingu under Bolsonaro"]

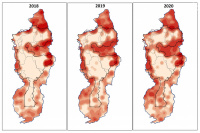

In the last three years, deforestation within Protected Areas has varied from 30% in 2018 to 34% in 2020. This process reveals the displacement of deforestation within indigenous territories and traditional populations, a trend that was evident in 2019, the first year of the Bolsonaro government, when there was a 38% increase in deforestation within Indigenous Lands and 50% within Conservation Units in the basin.

Between 2018 and 2020, a period that coincides with the election and the first half of President Jair Bolsonaro's term, 513,500 hectares were deforested in the Xingu basin. The area is equivalent to 6 times that of New York city (USA). Currently, 149 trees are cut down every minute.

Instead of implementing measures to protect the Xingu, the government promotes a scenario of total impunity through speeches favorable to the unconstitutional reduction of Indigenous Lands and the legalization of destructive activities, such as mining, in addition to weakening inspection actions.

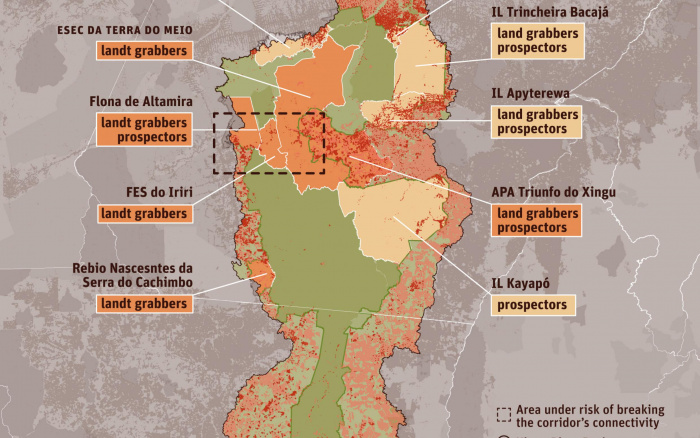

Breaking connectivity in the Xingu Corridor puts the Amazon at risk

“Grileiros” (land grabbers) groups advance on Protected Areas in the Iriri region, between the municipalities of Novo Progresso and São Félix do Xingu, in the state of Pará. Deforestation threatens to cut the forest strip in half, ending the connectivity of this large forest massif.

And far from being an isolated fact, it can impoverish the forest, affecting thousands of species that depend on their connection, further weakening their ability to resist changes around them.

It is estimated that 17% of the original coverage of the Amazon has already been deforested, bringing the forest closer to the “point of no return”. That is, the moment when the degradation will reach a limit after which the forest will no longer be able to exist as we know it today, giving space to a drier and more vulnerable vegetation, without the capacity to continue exercising its function of providing rain, essential all over South America. The destruction of the Xingu Corridor can accelerate this process, its protection, therefore, is fundamental for the guarantee of the forest, its people and the climate on the planet.

Deforestation exploded

Between 2018 and 2020, at least 513,500 hectares of deforestation were detected in the Xingu hydrographic basin.

In the last three years, deforestation within Protected Areas has varied from 30% in 2018 to 34% in 2020. This process reveals the displacement of deforestation within indigenous territories and traditional populations, a trend that was evident in 2019, the first year of the Bolsonaro government, when there was a 38% increase in deforestation within Indigenous Lands and 50% within Conservation Units in the basin.

The rates reflect the expectation, in that year, of the easing of environmental laws and the precariousness of policies to combat deforestation, as well as the effective reduction of lawn and enforcement actions.

In the three years of monitoring, 66,500 ha of deforestation were detected in the Indigenous Lands. As of October 2018, deforestation began to intensify in some territories, such as the Cachoeira Seca, Ituna Itatá, Apyterewa and Kayapó Indigenous Lands. In 2019, this trend was consolidated in other areas and there was an explosion in deforestation, the result of invasions, theft of wood, illegal mining and land grabbing.

In 2020, deforestation within Conservation Units and Indigenous Lands decreased by 6% and 49%, respectively, while in its surroundings it increased by 23%. The reduction in deforestation within the Protected Areas occurred after concentrated actions of inspection of Ibama in critical Indigenous Lands of the basin, such as the Cachoeira Seca and Ituna Itatá, whose indexes showed a drastic reduction in the beginning of 2020. The cancellation of the inspection actions in the last year, however, threatens to reverse this trend and deforestation may start to grow again.

From 3 hectares deforested in May in Trincheira Bacajá, deforestation jumped to 411 hectares in December, an increase of 12,980%, in the following months, between September and December, another 1,847 ha were deforested in this IL. At Apyterewa, deforestation increased by 393% in the month following the suspension of operations, and continued to grow: between July and December, 5.8 thousand hectares were deforested, 1,287% or almost 14 times more than the total deforested between January and June.

Xingu Protected Areas Corridor: diversity, water and shield against destruction

The Xingu River basin comprises an area of approximately 53 million hectares in the states of Pará and Mato Grosso and covers a great diversity of peoples and ecosystems, from dense and lowland forests in the Amazon biome to areas of typical Cerrado vegetation. The basin contains one of the largest continuous mosaics of Indigenous Lands and Conservation Units on the planet: the Xingu Protected Areas Corridor.

With 23 Indigenous Lands and nine Conservation Units, the Corridor is considered one of the regions with the greatest socio-biodiversity in the world, housing 26 indigenous peoples and hundreds of riverside communities. For centuries these traditional peoples have managed and protected their forests, which contain an immense set of species of plants and animals, some of which are still unknown to science. With an area of more than 26.5 million hectares, the Corridor has a crucial role in protecting the Amazon and the climate.

The region provides invaluable environmental services to the planet, from the protection of rivers and springs to climate regulation at local, regional and global levels. Its vast forests represent one of the largest and most stable carbon reserves in the eastern Amazon, storing approximately 16 billion tons of CO2.

It is estimated that its trees release into the atmosphere, through evapotranspiration and the production of volatile organic compounds that act as rain condensation nuclei, from 880 million to 1 billion tons of water per day, a volume similar to that of the Xingu river flows into the Amazon in the same period.

Water is transported by the so-called “flying rivers” to the central-west, southeast and south regions of Brazil, providing rain for cities and fields, essential for the maintenance of agricultural activity.

Isabel Harari

ISA

Imagens:

Arquivos:

| Anexo | Tamanho |

|---|---|

| 36.81 MB |