Você está na versão anterior do website do ISA

Atenção

Essa é a versão antiga do site do ISA que ficou no ar até março de 2022. As informações institucionais aqui contidas podem estar desatualizadas. Acesse https://www.socioambiental.org para a versão atual.

What changes (or is left) for indigenous peoples with president Bolsonaro’s reforms in Brazil?

quinta-feira, 07 de Fevereiro de 2019

Esta notícia está associada ao Programa:

On the day the indigenous people are out on the streets for their 1st official protest against the new administration, ISA publishes its last report on the ministerial reform. The rural caucus has opened the path for keeping its promise in putting an end to [indigenous] land demarcations

Jair Bolsonaro’s adversaries can’t complain that his positions are ambiguous, at least when it comes to indigenous peoples’ rights. Years before the rural caucus’ campaign against [indigenous] land demarcation, he already made clear what he thought of the indigenous people, no subtleties or nuances.

Jair Bolsonaro’s adversaries can’t complain that his positions are ambiguous, at least when it comes to indigenous peoples’ rights. Years before the rural caucus’ campaign against [indigenous] land demarcation, he already made clear what he thought of the indigenous people, no subtleties or nuances.

In 2004, at a commission at the Chamber of Deputies, he called them “smelly, uneducated, who don’t speak our language”. In 2008, he told indigenous leader Jecinaldo Barbosa he should “go eat grass outside to stick to his origins”, after Barbosa threw a glass of water at him during a quarrel at a hearing, also at the Chamber of Deputies. Between 2017 and 2018, on different occasions, Bolsonaro affirmed the country had an “industry of demarcations” and things like “if it’s up to me, there will no longer be demarcation of indigenous lands”. He also defended that indigenous people were in an “inferior situation” and compared them to “animals in a zoo”.

On the day the Articulation for Indigenous People of Brazil (Apib) is carrying out, countrywide, the first large-scale popular mobilization against the government of Bolsonaro, the third and last report of the in-depth analysis carried out by ISA of the most drastic ministerial reform since the Collor administration (1990-1992) shows how and why the new administration has opened the way for the dismantling of Indigenous policies, as we demonstrated in the case of agencies and initiatives working for environmental and quilombola causes.

Radical reform

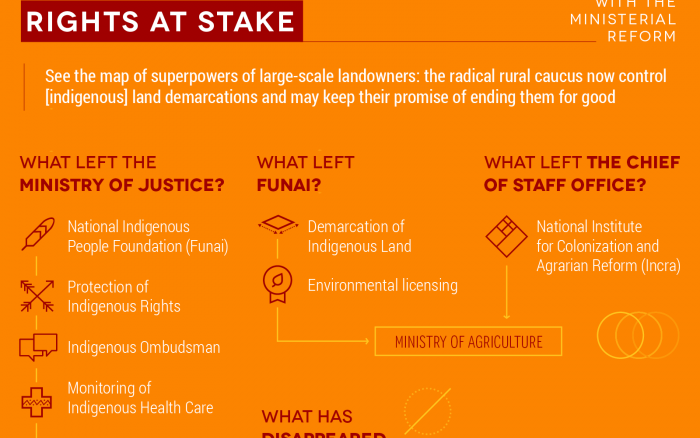

The restructuring of the agencies linked to indigenous rights can also be considered the most profound in nearly 30 years. Subordinated to the Ministry of Justice (MJ) since 1991, the National Indigenous Peoples Foundation (Funai) is now nestled under the Ministry of Family, Women, and Human Rights Issues, led by controversial Damares Alves. The attribution of demarcating Indigenous Lands (ILs) and providing opinions on the environmental licensing of projects with impacts on these areas were transferred from the indigenous agency to the Secretariat of Land Tenure Matters (Seaf) of the ‘superministry’ of Agriculture (Mapa), led by the rural caucus, historical adversaries of demarcations and Bolsonaro’s main support base. The information that has circulated up to now – not yet officially confirmed – is that the two roles would be led on a daily basis by an entity that is still to be created within the National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (Incra), now also linked to Seaf. Incra continues to be responsible for agrarian reform and titling of quilombo lands.

The chain of command of these policies is now in the hands of the most radical wing of the rural caucus. The new Minister of Agriculture is the federal deputy Tereza Cristina (DEM-MA). The Secretary for Land Affairs is Luís Antônio Nabhan Garcia, president of the Rural Democratic Union (UDR). Its deputy secretary is Luana Ruiz, who advocates for several landowners against [indigenous] land demarcation. The recently exonerated Funai director Azelene Inácio is the main candidate to control the Incra indigenous agenda (see who's who in the box at the end of the report).

Conflict of interests

"When you move the responsibility of the [indigenous land] demarcation to Mapa, the organ is being equipped by people completely opposed to demarcation. From our point of view, it is a deviation from its purpose ", criticizes Luís Eloy Terena, Apib’s legal adviser. He adds that indigenous peoples have not been consulted on the changes, as determined by Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO), ratified by Brazil. As early as the beginning of the month, Apib published a note and sent a representation to the Attorney General's Office (PGR) against the new ministerial layout.

The founding partner of ISA and former president of Funai Márcio Santilli agrees that the new organizational chart creates a conflict of interests between farmers and indigenous people. "We are talking about the dispute over what is left of the Brazilian territory. The federal administration should plan and mediate policies that could consolidate the occupation in a peaceful manner, contemplating the rights of different populations. However, what this government is doing is removing the treatment of the indigenous issue from the paradigm of Justice and Law to submit it to the interests of the large landowners," he says.

Santilli predicts that the result of the ministerial restructuring will be the halting and legal prosecution of demarcation procedures. "This will be the tonic: an omissive government wanting to back down, as the Constitution forces it to complete the demarcations. The tension will end up the Judiciary branch," he bets.

Another proposal under study in the new management is the creation of an interministerial council to decide on the demarcations, a model implanted in the Military Dictatorship so praised by Bolsonaro. The collegiate tends to include Agriculture, Human Rights, Environment, Defense and Justice, as well as the Chief of Staff and Institutional Security Office. Thus, interests such as those in the mining and energy sectors should have an even more direct influence on the complex and time-consuming demarcation process. The council would make a decision after the first of its identification stages. Thus, the fear is that many processes will become stillbirths.

Revision of demarcations

Nabhan Garcia tries to minimize the president's promises and denies that the demarcations will be paralyzed. "One thing is the campaign. It's another thing to be a government. In the campaign, what we heard from the then candidate Jair Bolsonaro was the following: there will be no hastened, ideological and political, decision on demarcation", he says.

Without elaborating on how, Garcia insists that he intends to review all land regularization processes at the federal level, including agrarian reform, quilombos and ILs. The secretary assures that the government will try to reverse or annul processes in which flaws or irregularities are identified, including the indigenous demarcations already completed.

"When Bolsonaro proposes this revision, it stimulates immense legal insecurity and instability among the Government, indigenous people, rural producers who have been removed from the areas or who are still involved in the land dispute," argues ISA lawyer Juliana de Paula Batista. She adds that, according to legislation, only a solid reason which demonstrates an "unfixable vice" can be used to justify the reanalysis of demarcation procedures. For Batista, by indiscriminately questioning them, the government encourages conflicts and invasions.

"Any administrative act may be reviewed if it has any nullity or if there is a relevant public interest. That is not to say that there is any doubt about the demarcation processes done so far," prosecutor Antônio Carlos Bigonha said at an event at the Attorney General's Office in Brasilia last week. He evaluated that procedures with problems are the exception. "What exists in Brazil today are regularly demarcated lands," he concluded.

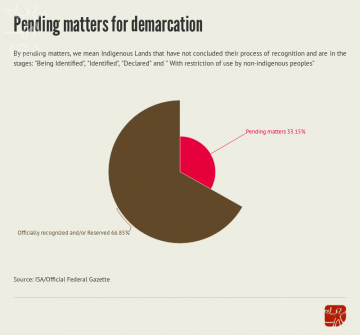

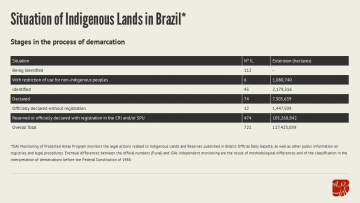

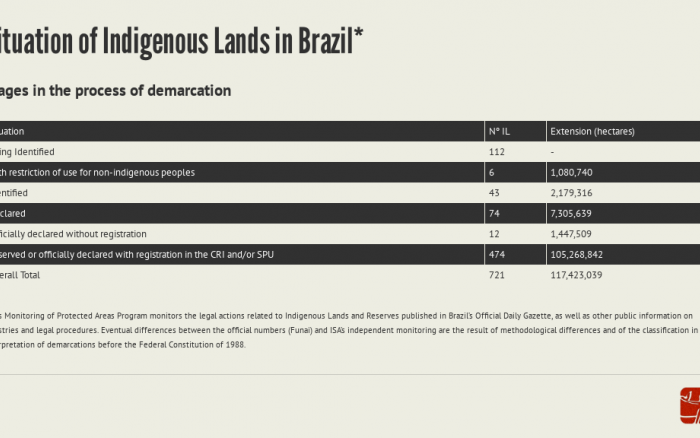

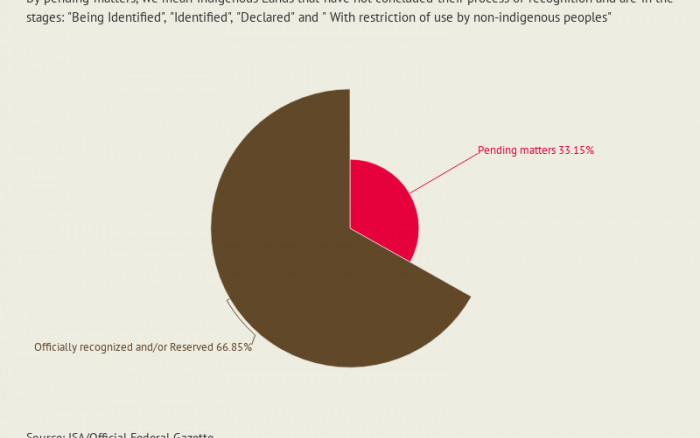

The threat of reversal or permanent halting of processes for the recognition of territories comes after years of stagnation in its course. It is worth remembering, however, that only a third of the outstanding issues remain. In addition, the rural caucus discourse that there are too many ILs in the country does not correspond to the truth. While these areas occupy just under 14% of the national territory, rural properties represent almost 30%. Outside of the Legal Amazon and in the states with the most conflicts over ILs, the extent of these territories is small, even more compared to the total extent of rural properties. Brazil continues to be one of the countries with the greatest land concentration in the world: only 93,000 latifundia or 1.6% of the total rural properties account for 47% of the total land area.

Funai in pieces and thrown into a legal limbo

The ministerial reform emptied and shredded Funai. But the problem may be more serious because a legal and administrative limbo may have been created that calls into question the executive capacity of the bodies involved with indigenous matters.

The Provisional Measure (MP) 870/2019 and the decrees that restructured the ministries mention only the loss of the roles of demarcating and providing opinions about licensing. The point is that the rest of the legislation still in force continues to assign Funai both tasks and the role of protecting indigenous rights in general. The MJ also continues to be cited in the rules on demarcation and protection of Union assets, as is the case with ILs.

Indigenous land in Brazil (especially the Legal Amazon)

The Provisional Measure and decrees also do not specify the transfer of Funai structures, budget and positions to Mapa and Incra. There is still much doubt as to how this will be done. Public officials complain about the lack of information.

Internal documents and messages between officials that the report had access to led us to believe that more roles, other than those mentioned in the reform, can migrate to Incra, such as monitoring ILs, producing maps and even the removal of non-indigenous peoples from the territories.

Public officials, indigenists and indigenous people interviewed by ISA point out that the state has invested in the qualification of employees and the accumulation of technical expertise in Funai for decades. They question whether Incra and Mapa will be able to carry out the actions developed by the indigenous body.

Licensing

In the case of licensing, a source from the institution who asked not to be identified foresees two alternatives in light of the administrative imbroglio: Funai would have to manifest itself after the licenses were granted or it would become the "intervenor of the intervenor", i.e. it would subsidize Incra with advice. Result: more bureaucracy and delay in the authorization of projects. The legislation determines that the Brazilian Institute of the Environment (Ibama) must license projects with impacts on ILs. Funai had and now Incra has an advisory role in these cases.

"Do you think Mapa will say anything against a hydroelectric dam, highways, railroads, nuclear power plants? It is one thing for Funai to talk about impacts on indigenous peoples and lands. Another thing is for Mapa to talk about it," the source said. The source said says that since the Lula administration, in most cases related to large projects, the position of the technical team on the licenses did not prevail. With the transfer of the task to bodies with no accumulated experience and knowledge and under even more direct political pressure, therefore, the situation would tend to worsen.

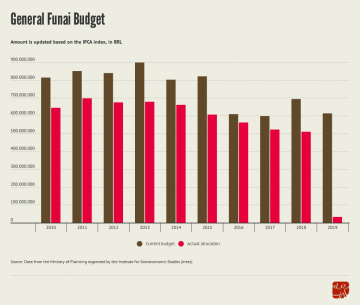

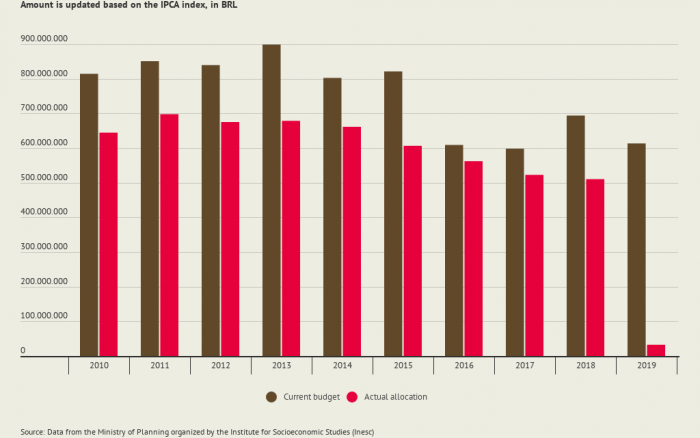

Licensing coordination also suffers from the same problem of lack of staff as does the rest of Funai. In all, the institution has 4,300 open positions, but only 2.3 thousand servers working, a gap of 46%. The problem worsens year by year with retirees. In addition, the budget allocation for 2018 was equivalent to that of 2008. Between 2010 and 2019, it fell 25% (see infographic).

Dispute between the evangelical and rural caucuses

The new organizational chart of the indigenist policy began to be conceived after the fall of Dilma Rousseff.

Headquarters of the Evangelicals in Congress, the PSC [political party] negotiated with Michel Temer to support the impeachment in exchange for control of Funai. The party's nominee to preside the institution at the time was Antônio Fernandes da Costa, but he ended up clashing with the then Minister of Justice, deputy Osmar Serraglio (MDB-PR) of the rural caucus.

The crisis was solved by Costa's exoneration and the division of the main positions of leadership between the two groups. Retired general Franklimberg Ribeiro de Freitas ended up winning the support of the evangelicals to assume the presidency of the agency, in May of 2017. In turn, the rural caucus appointed the two most important directors, of Administration and of Territorial Protection, the latter in charge of the identification and delimitation of ILs. In a short time, the representatives of the two groups again became entangled. The new crisis was solved with the departure of Franklimberg, in April of 2018.

The solution found by Bolsonaro to resolve the power dispute was the dismantling of Funai. The result is that the rural caucus is now in charge of the entire land policy of the new government, and the evangelical base in Congress will control the initiatives of assistance aimed at the Indians. The return of Freitas to the command of Funai after the inauguration of Bolsonaro also guarantees the influence of the military on the institution.

What is left of the indigenist policy?

The structure of the Regional Coordination (CR) and Local Technical Coordination (CTL) is subordinated to Funai. They play an important role in the management and protection of ILs and in the access of Indigenous people to documents and social benefits, for example. They also support the preparation and implementation of the Territorial and Environmental Management Plans of these areas. These documents provide for economic alternatives, instruments of territorial control and conservation, among others. The problem is that this policy is now homeless, because of the extinction of the Ministry of Environment's (MMA) Extractivism Secretariat, responsible for the matter until last year.

The formal competencies to protect indigenous rights in general and to monitor health care actions for communities have also been transferred from Justice to the Human Rights agenda, as well as the National Indigenous Policy Council (CNPI). The ministry headed by Damares Alves should also promote actions for indigenous women, according to the decree that instituted it.

The ministerial reform also included the coordination of initiatives to promote agroextractivism and the production of traditional communities, which had previously been allocated to the extinct Secretariat of Extractivism of the MMA, among the competencies of the Department of Productive Structuring of the Secretariat of Family Agriculture and Cooperativism of the Ministry of Agriculture. The problem is that among the prerogatives of the new Mapa secretariat there is no longer any mention of indigenous peoples.

Who is who in the indigenist policy of the Bolsonaro administration

Damares Alves, Minister of Family, Women, and Human Rights Issues

Alves is a pastor and worked as an advisor to evangelical parliamentarians for years. She became known her militancy against the legalization of abortion and sex education. In her first press conference after being announced, she reinforced the expectation that the demarcations should indeed be relegated by the Bolsonaro administration: "Indians are just about land," she said. The Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office has a lawsuit against an organization founded by Alves for using Karitiana indigenous people as actors of a film that intended to denounce infanticide. The practice is not part of the tradition of this community. According to this week’s edition of the magazine Época, Alves supposedly removed an indigenous child from her family irregularly. The child lives with her since she was six years old.

Tereza Cristina, Minister of Agriculture

The federal deputy re-elected by the DEM party of Mato Grosso do Sul, became president of the Parliamentary Front for Agriculture (FPA) in early 2018, but was notable for leading the special commission that approved, in the same year, the Draft Bill (PL) nº 6.299/2002, which facilitates the sale and use of agrochemicals in the country. Because of this, she was nicknamed by her counterparts as "Muse of Poison". Both her electoral campaigns were financed by large agribusiness companies, including agrochemicals. Cristina defends the opening of the ILs to large-scale agricultural activity and even asked the Minister of Justice to suspend the National Policy for the Sustainable Development of Peoples and Traditional Communities. According to Folha de S. Paulo, she granted tax incentives to the JBS group while maintaining a partnership with the company, in 2013, at the same time as she held the post of state secretary of Agrarian Development and Production. Still according to the newspaper, the minister received campaign donations from a farmer accused of killing an indigenous person in a land dispute. The Mapa press office did not return requests for an interview with the minister up to the time the report was closed.

Nabhan Garcia, Secretary for Land Tenure Matters in the Ministry of Agriculture

He was a strong candidate for minister, but ended up in a lower position, despite being considered close to Jair Bolsonaro. He is a licensed president of the Rural Democratic Union (UDR), a conservative organization born in the late 1980s in reaction to the rural workers 'and peasants' movement, which is currently not considered representative even by leaders of the agricultural sector. Therefore, his indication is not a consensus in the rural caucus environment. Garcia is a historical opponent of agrarian reform, formalization of ILs and quilombos. He insists that there are "ideological and political" influences in these processes. He is also one of the government's most critical environmental watchdogs and likes to repeat, as the president, that there is a "industry of fines" in the country. The secretary defends the use of weapons against land occupations and guarantees that he will not dialogue with social movements that adopt land occupation practices. He interrupted the interview, without clarifying those points, after being informed that the purpose of the conversation was to post on a civil society organization's website - although he had already been communicated about it twice, in advance, by telephone and WhatsApp. Garcia said he did not give interviews to "NGOs".

Luana Ruiz Silva de Figueiredo, assistant secretary for Land Tenure issues in the Ministry of Agriculture

Figueiredo is a lawyer responsible for several lawsuits against demarcations. Her family is bringing a lawsuit to recover land at IL Ñande Ru Marangatu, in Antônio João (MS). She was at the local rural union meeting that preceded the attack by rural landowners on indigenous people who had reoccupied a small fraction of the area in 2015. The then federal deputy and current Minister of Health, Luiz Mandetta, was also at the meeting and was with the farmers. The attack left dozens of wounded Indians and led to the murder of the indigenous person Simião Vilhalva. At the time, the union was headed by Luana's mother, Roseli Ruiz. Even after the crime, the lawyer continued to advocate the use of weapons to combat land occupations. The report contacted her, but she declined to give an interview (see more videos of the lawyer).

Azelene Inácio, pointed as the possible person to conduct the Indigenous agenda in Incra

She was appointed to the Funai Territorial Protection Directorate by the rural caucus group but was exonerated after the MJ requested that she leave the position, based on an official document from the MPF. Prosecutors considered that there was "conflict of interest and behaviors that were incompatible with administrative morality" during her appointment. Her appointment to a position at Incra, therefore, disregards the determination of Minister Sergio Moro. Azelene defends large-scale agriculture in ILs and is married to lawyer Ubiratan de Souza Maia, who was sentenced to return about BRL 120 thousand to indigenous communities of Santa Catarina for the illegal practice of leasing land in these areas. The report was able to contact Azelene, but she said she could not answer and asked to call again later. After that, she could no longer be located.

Oswaldo Braga de Souza

ISA

Imagens: